2013 turned out to be a really bad year for me, physically that is. First, I broke my left ankle and then a few months later broke the right. Perhaps a little investigation into bone density was in order? The first one wasn’t so bad because after six weeks of no-weight bearing I could at least drive. The other one, not so much. In all, I spent nearly eight months confined to quarters. On the plus side, I had copious amounts of time to write. (Sort of like during the pandemic!)

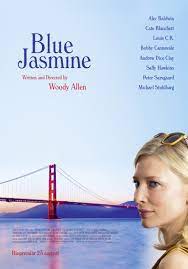

While convalescing, a friend decided to rescue me for the evening and took me to see Blue Jasmine. The critics couldn’t find enough stars for their reviews, apparently, and many raved beyond the stellar limit of five. Now, I’m a huge fan of Woody Allen movies, even when others trash them. I get his sense of irony and humor, and embrace his sad-sack characters without question, so when this one got such an amazing review, I jumped at the chance to go. Okay, I didn’t jump. I limped, hobbled on my crutches, hot pink cast in tow… on my toes.

I left angry and frustrated and so did my companion. My first time out of the house in weeks and I sat through two hours of miserable characters who whined and complained, did terrible things, and in the end were exactly where they were at the beginning of the movie. In my mind, Woody broke all the rules for writing characters, especially the protagonist. Of course, Woody is world famous, and rich, as a direct result of his writing and movie-making, so who am I to criticize him? But really, in my humble opinion, he missed the mark in every way. Your protagonist has to do something and you have to care about it.

For example, your protagonist should…

- Be likeable, for the most part. His character traits might be despicable with few redeeming qualities, but he has to have at least one. Many characters can be difficult to love. Take Tony Soprano, Lena Dunham’s character in the HBO series Girls, or Lisbeth Salander in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. Even if they make us cringe sometimes, we find a heart in them and we root for them. We get a thrill imagining what it would be like to be them.

- Do something that matters! Two hours and the characters lied, cheated, stole, swindled, embezzled and in the end had absolutely nothing to show for it. Maybe they did stuff, but I didn’t care about it because something must change and it didn’t. They weren’t better or worse off in the end, but exactly in the same place.

- Be on a quest with a goal. These characters spun in circles the entire time and they didn’t pass go, didn’t collect $200- well they kinda did, but then they lost it and wound up penniless again. Even if you don’t want to embrace the “hero model” your protagonist should be complicated, in conflict, fighting for something. Well, these characters did plenty of fighting, there was lots of conflict, but absolutely no resolution!

- Be the prime mover of the story line. He shapes the story and usually is reshaped in return. Not here. One main character leaves her obnoxious boyfriend, gets involved with some seemingly wonderful new guy, but then he turns out to be married and she goes back to the other guy. The main character lies and manipulates another guy after her husband goes to jail for swindling people out of their hard-earned savings and when he finds out, he dumps her. Well, duh, I could see that coming a mile away. Then she tries to rekindle her relationship with her son and you hope there is some redemption at hand, but he tells her to go to hell and he never wants to see her again.

- Be active, not passive. He should act, not react in the story. Otherwise, you create a boring protagonist. I’d rather loathe the protagonist than be bored by him.

- Center the story. He defines the plot and moves it forward. His fate determines whether the story is a tragedy or comedy. Maybe Woody meant for this to be a tragedy, I could almost get on board with that, except that you have to care about the people in a tragedy and I couldn’t care less about these characters. Any of them!

Despite the universal praise from reviewers and I’m sure many would take issue with my comments, I found its fractured protagonist too abrasive to warrant my empathy. If I wanted to spend two hours with someone involved in nightmares, anxiety attacks and a nervous breakdown I’d call my next-door neighbor, who I admittedly try to avoid at all costs. One can only take so much wry melancholy, scathing satire, and dark-hearted asides and call it entertainment. I could get that for free next-door.

Up Next? Writing the Antagonist.